An Antiwar Voice from the Russian Left – Interview with Ilya Budraitskis

Interview with a well-known Russian intellectual and activist on the anti-war movement

Spotlight

-

Πρώην Ρωσίδα κατάσκοπος αποκαλύπτει πώς αποπλανούσε ερωτικά τους «στόχους» της

-

Η Κέιτ Μίντλετον και ο πρίγκιπας Γουίλιαμ γιορτάζουν την επέτειο του γάμου τους με μια άγνωστη φωτογραφία

-

Εντατικοί έλεγχοι της Αστυνομίας για διακίνηση κροτίδων και βεγγαλικών ενόψει Πάσχα

-

Ένα (μεγάλο) ερώτημα ψάχνει απάντηση στο Λίβερπουλ

Born in 1981 Ilya Budraitskis comes from a generation that grew up in the harsh realities of Post-Soviet Russia, but did not opt for either western-style liberalism or the varieties of nationalism (including what can be defined as ‘Putinism’). Instead, he attempted to reconnect with a critical Marxist tradition. A historian by training he has been an outspoken critic of Putin but also a very insightful analyst of the social, political and ideological developments in Russia. His book Dissidenty stredi dissidentov (Dissidents among Dissidents), a collection of essays that appeared first in Russia won the prestigious Andrei Bely Prize in 2017 and recently was translated into English (Verso, 2022). From the moment the war in Ukraine started Budraitskis took a clear position against the war and is one of the most recognized left critics of the Russian government and its politics. Budraitskis had recently a discussion with Panagiotis Sotiris for In.

How did we arrive at this war? Which part is more responsible in your opinion?

I think that that definitely the main part responsible for this war is Russia. It was the decision made by the Russian Government, it was the decision made by President Putin. If it were not for this decision, we would not be having this war. Actually, if you look back at Putin’s speech at the moment of the beginning of the invasion, you can see him saying that “he had to do it”, that there was no other way for Russia to operate in this situation. In a certain way he tried to avoid the responsibility. This is psychologically understandable, but I think that we should be very clear in regards to the question of who made the decision. Because of course at any moment in a war there are circumstances and some context that made this war possible, but in all such situations there is always one side that started first. And from the Russian side in this situation it was not a decision just to start a war, it was a decision to start an invasion in the territory of another country, it was a clear plan to conquest this country, to change its government, to install some kind of occupation regime. So in this sense you cannot say it was some kind of defensive war. It was not an action that tried to prevent some attack against Russia. It is clearly a case of an aggressive war against another State.

Of course, this decision did not come out of nothing. There is a long history behind it and this history did not even start in 2014, with the annexation of Crimea and the conflict in Donbass. It started quite earlier. It started with previous attempts of the Russian Federation to secure its influence and its presence in the Post-Soviet space. It started in the early 2000s with the first “Maidan” in Ukraine with all the efforts of Russia to install some pro-Russia leadership and behind this history you see the very exact concept, the very exact approach of how the authorities of the Russian Federation understood their role in the Post-Soviet space and how they understood the nature of the other post-Soviet countries and especially Ukraine. They never believed that these countries have their own agency, that they exist in reality and that the Russian Federation could have some form of equal relation with them. The second important moment was that they denied any subjectivity of the peoples of these republics. It was this idea that only leaders, only elites matter. This is why Russia for two decades has been trying to work with the elites of Ukraine but not with the population, especially the Russian-speaking population of the Ukraine.

To what extent US and NATO policies in regards to Eastern Europe have been a contributing factor to the war?

Firstly, I want to make clear that I believe that this is not a war between Russia and the West. It is a war between Russia and Ukraine. Even in the situation were the West has been supporting Ukraine, it is not a part of this military conflict. In this sense, you cannot say that NATO is really participating in this war.

In what way the NATO and the US are responsible? I think that they are responsible in the sense that when you look at the developments during the past year, when it was clear that Russia was preparing the invasion and that it was sending troops near the border, at that moment there were two ways, two strategies to avoid the war.

One strategy would have been, from my point of view, a clear offensive strategy in the sense of “If you start the invasion we would immediately react militarily”. I believe that if there had been such a message from NATO, Putin probably would not have started the invasion.

The other strategy would have been to give Putin what he actually wanted, in some sense: to give him some guarantees that Ukraine will not join NATO in the coming decades. If there had been such written guarantees, as Putin asked in December, this would also have probably led Putin not to start the invasion for the moment. I personally don’t believe in it, but it was a possibility.

However, NATO and the US did something different. The strategy they choose was to provoke Putin, to refuse all his demands and at the same time they did not give clear guarantees in regards to the security of Ukraine. That was the most cynical and provocative strategy that you can imagine.

On the one hand they openly declared that Putin was going to invade, but on the other side they didn’t make any real steps to stop it. And this is definitely the responsibility of the West for this war.

To what extent can we say that there has been a “Ukraine problem” since 2014, or even before, in particular in regards to the situation around the so-called ‘people’s republics’ in Donbass?

What is the real base of the problem in Donbass? If you look at the Post-Soviet space, Kazakhstan for example or the Baltic States or Moldova, in all these countries you have significant Russian-speaking populations. In all of these countries, one way or the other, you have problems with the rights of Russian speaking populations, especially in regards to language, rights etc. Ukraine during the Post-Soviet era was not the most problematic country in regards to this. For example Kiev, the very capital of Ukraine had been mostly a Russian-speaking city and there was not a problem with it. There were TV shows and newspapers in Russian in Ukraine. There was not a problem with any public use of the Russian language. This was a situation different from the one you can find in the Baltic States were you have all sorts of problems.

The question of language was not a central political question in Ukraine, during the first Post-Soviet decade, in the 1990s and early 2000s. It became more and more important with the political polarization, because of the attempts by Russia and the West to influence Ukraine politically. This question was highly politicized. On a serious level this politicization started in 2005 when there was the first so-called “Orange Revolution”, when Russia backed presidential candidate Victor Yanukovych who failed at the presidential elections.

Then, that part of the Ukrainian elites that was more inclined towards collaboration with the Kremlin, not with Russia as a State, but with the Kremlin as a state apparatus, started to present themselves as the representatives of the Russian-speaking population.

On the other side of the political frontier, the pro-European forces in the Ukrainian elite used the idea of Ukrainian language as the only official language. For most Ukrainians even in 2014 there was not such a clear definition of identity. You could be Ukrainian and speak Russian. But the movements inside the elites forced people to choose one identity over the other. This made the question of language a political question. If you look at the current Russian propaganda line, in Putin’s speeches etc, you can find this idea of the so-called “Russian world” which is based on an absolute identity between language and citizenship of Russian Federation, the state interest and the use of the Russian language. Basically it means that if you speak Russian you should be defended by the Russian state and you should support the Russian state, because the Russian State is the only force that is directly linked to your mother tongue. This conception is the classic nationalist-chauvinist one from the 19th century. Many people in the other nation-states of Europe could easily recognize it. For example, you in Greece you can understand this idea that all Greeks, linguistically and culturally, should relate to the same State and what kind of conflicts this idea could provoke.

Russian media insist on the existence of a certain ‘patriotic’ feeling within Russian society and in general project an image of increased popularity of Putin and the Russian government. Is this true or is it just propaganda?

Of course there was no referendum on the war in Russia. This question was not discussed publicly in Russian society. Immediately after the start of the invasion, the debate about the nature of this war criminalized. According to a law that we have now in Russia, if you reproduce any information that is different from the official information coming from the Ministry of Defense, you are distributing “fake news”, fake information about the Russian Army and you can be imprisoned up to 10 years for this action. It means that as a Russian citizen you have only two ways to deal with this situation.

One strategy is to agree with it. This means that you simply affirm your normal existence as a Russian citizen. Otherwise, you refuse it, but this means that you immediately confront the State, you confront “public opinion,” and you confront the country.

Russia has been a deeply depoliticized country. Most of institutions of public life, the independent media, the opposition parties and basic rights, such as right of assembly in public space were already eliminated when the conflict started. The only way to live in the country is to accept any action from the government.

The high level of approval of the military operation is a demonstration of this kind of depoliticized conformism which is the main condition of Russian society, which has been ‘trained’ for years. It is also important that all this huge support of Putin in regards to the military operation is indicated only by opinion polls. And you can imagine what opinion polls mean in the country where people have a fear to express publicly their thoughts and opinions. It means that if any outside member of society, namely not a member of your family or a friend or a person that you can trust, asks you “what do you think of the ‘Special Military Operation’?” – it is important to note that you cannot call it a war, this is forbidden in Russia – you immediately mirror this question with responding “yes, of course, I totally support my president.” Simply because you want to live your own private life and you do not want problems for yourself or your family.

What is the real level of support for this war? What do they really discuss in private spaces? We do not know, because politically these feelings are non-existent. We know that there is a tiny minority who openly express their disagreement and their anti-war position. But you need to be politically motivated to do this.

However, even in the official public opinion polls you have something like 15% of people who are ready to declare publically, to declare in front of the pollster, that they oppose this war. This is a significant number in this situation.

What can you say about the resistance to the war in Russia?

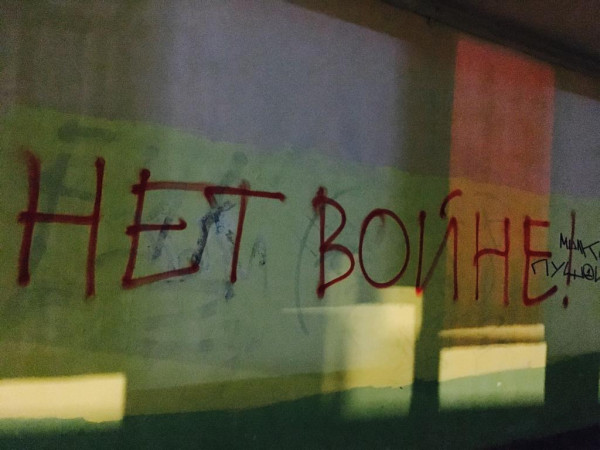

In the first two weeks of the war there were every day or every two days illegal rallies (because all rallies are illegal in Russia) against the war in the big cities, like Moscow, St Petersburg, Yekaterinburg etc. The reaction from the authorities to these rallies was quite brutal. In the first week of these rallies around 15.000 persons were detained. This means that they had to spend some day or even weeks in police stations, they had to pay very high fines, and if they were students, they were expelled from their universities. After this wave of repression against this anti-war movement, it lost any sense of organized form. There are no rallies against the war now in Russia. However, there are many acts of individual protest. Some people during the night might write some antiwar graffiti, or put some leaflets or destroy these Z symbols that you have basically everywhere in Russia. There still some individual picket lines. So people stand with a poster with an antiwar message in the public space, in squares or streets, but all these forms of action are also risky. But if you stand in an individual picket line, you can also be arrested, after a couple of minutes, spend some days in a police station and be fined. The active antiwar resistance in Russia is very low, not because of a huge support for this war, but because of the fear and pessimism that you have in society. I believe that this situation could change. It will be difficult for authorities to hide these serious losses in the war, the soldiers killed in Ukraine. A month ago the Ministry of Defense announce that 1300 soldiers had been killed, which was too small a number to believe, and it was a month ago. For the last month there has been no official announcement and it seems as if the government is trying to hide the very fact that the country is in a war condition. This is the essential aspect of the propaganda. You cannot even use the word war and there is an illusion of normal life promoted by the official propaganda. You also have this idea that it will end soon and that this is a short term military operation that will end in a week or two. There are still a lot of people in Russia who distance themselves from what is going on, who can answer to the question about what is going on in the Ukraine with an answer like “we are not interested in politics”. This also expresses this very deep level of depoliticization of Russian society.

You have been one of the most well-known left-wing critics of the Russian government and the policies of Vladimir Putin. To what extent can we talk about the emergence of a ‘new Left’ in Russia and what’s the role of the traditional communist left which seems to support Putin?

From the beginning of the war you had a deepening split in the so-called Left in Russia. On the one side the leadership of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation played a very shameful role by supporting this war. On the other side, the only members of Russian Parliament who openly disagreed with the invasion were three members of the Communist Party. Even in the Communist Party, especially at the level of rank and file members and activists you have polarization. There are many members of the Communist Party who are in disagreement with the positions of their leaders. The same process you have in some Stalinist or Soviet-nostalgic groups who also split around these questions. You have groups like Left Front or Russian Communist Workers’ Party, where the leadership mostly supported the war but many rank and file members or even minorities within the leadership left their organizations in disagreement with the pro-war position of their leaders. Also you have a lot of New Left or antistalinist groups and trotskyist or anarchist groups who opposed the war from the first moment and took part in the antiwar demonstrations. There is also a significant role played by the feminist movement. You have now a network called Feminist Antiwar Resistance, which is doing some propaganda work and is quite visible.

I believe that after the end of this crisis and after the end of the war which would probably lead to some crisis of this regime that would lead probably to some kind of reconstruction of this regime, the Left in Russia will somehow also be reconstructed. It is possible to reconstruct the Left on the basis of those members of very different groups (from the Communist Party to the Radical Left) that opposed the war and can help reconstruct the Left in Russia after this war.

Ακολουθήστε το in.gr στο Google News και μάθετε πρώτοι όλες τις ειδήσεις

Αριθμός Πιστοποίησης Μ.Η.Τ.232442

Αριθμός Πιστοποίησης Μ.Η.Τ.232442